If the boss asks you to work 50 hours, you work 55. If she asks for 60, you give up weeknights and Saturdays, and work 65. Odds are that you’ve been doing this for months, if not years, probably at the expense of your family life, your exercise routine, your diet, your stress levels and your sanity. You’re burned out, tired, achy and utterly forgotten by your spouse, kids and dog. But you push on anyway, because everybody knows that working crazy hours is what it takes to prove that you’re “passionate” and “productive” and “a team player” — the kind of person who might just have a chance to survive the next round of layoffs.

This is what work looks like now. It’s been this way for so long that most American workers don’t realize that for most of the 20th century, the broad consensus among American business leaders was that working people more than 40 hours a week was stupid, wasteful, dangerous and expensive — and the most telling sign of dangerously incompetent management to boot.

It’s a heresy now (good luck convincing your boss of what I’m about to say), but every hour you work over 40 hours a week is making you less effective and productive over both the short and the long haul. And it may sound weird, but it’s true: the single easiest, fastest thing your company can do to boost its output and profits — starting right now, today — is to get everybody off the 55-hour-a-week treadmill, and back onto a 40-hour footing.

Yes, this flies in the face of everything modern management thinks it knows about work. So we need to understand more. How did we get to the 40-hour week in the first place? How did we lose it? And are there compelling bottom-line business reasons that we should bring it back?

The most essential thing to know about the 40-hour work-week is that, while it was the unions that pushed it, business leaders ultimately went along with it because their own data convinced them this was a solid, hard-nosed business decision.

…

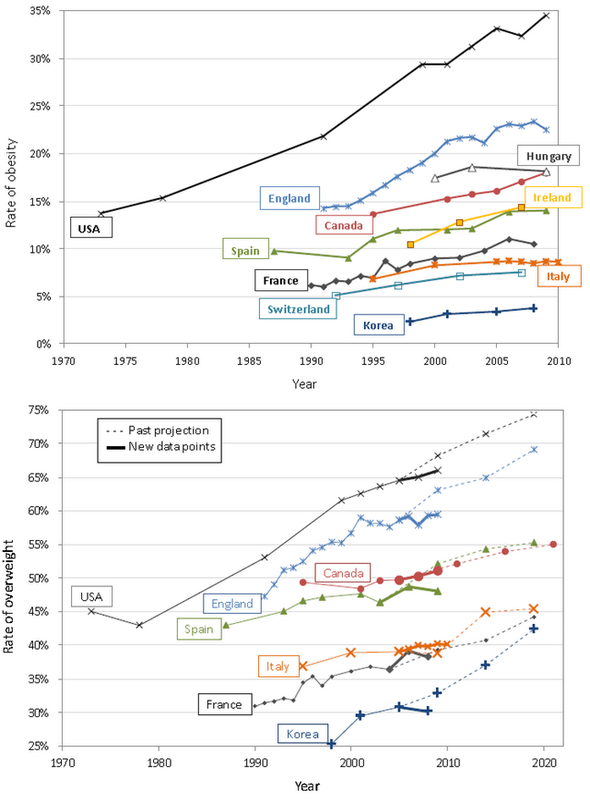

By the eighth hour of the day, people’s best work is usually already behind them (typically turned in between hours 2 and 6). In Hour 9, as fatigue sets in, they’re only going to deliver a fraction of their usual capacity. And with every extra hour beyond that, the workers’ productivity level continues to drop, until at around 10 or 12 hours they hit full exhaustion.

…

Without adequate rest, recreation, nutrition and time off to just be, people get dull and stupid. They can’t focus. They spend more time answering e-mail and goofing off than they do working. They make mistakes that they’d never make if they were rested; and fixing those mistakes takes longer because they’re fried. Robinson writes that he’s seen overworked software teams descend into a negative-progress mode, where they are actually losing ground week over week because they’re so mentally exhausted that they’re making more errors than they can fix.

The Business Roundtable study found that after just eight 60-hour weeks, the fall-off in productivity is so marked that the average team would have actually gotten just as much done and been better off if they’d just stuck to a 40-hour week all along. And at 70- or 80-hour weeks, the fall-off happens even faster: at 80 hours, the break-even point is reached in just three weeks.

…

So, to summarize: Adding more hours to the workday does not correlate one-to-one with higher productivity. Working overtime is unsustainable in anything but the very short term. And working a lot of overtime creates a level of burnout that sets in far sooner, is far more acute, and requires much more to fix than most bosses or workers think it does. The research proves that anything more than a very few weeks of this does more harm than good.

…

Knowledge workers actually have fewer good hours in a day than manual laborers do — on average, about six hours, as opposed to eight. It sounds strange, but if you’re a knowledge worker, the truth of this may become clear if you think about your own typical work day. Odds are good that you probably turn out five or six good, productive hours of hard mental work; and then spend the other two or three hours on the job in meetings, answering e-mail, making phone calls and so on. You can stay longer if your boss asks; but after six hours, all he’s really got left is a butt in a chair. Your brain has already clocked out and gone home.

…

The other thing about knowledge workers is that they’re exquisitely sensitive to even minor sleep loss. Research by the US military has shown that losing just one hour of sleep per night for a week will cause a level of cognitive degradation equivalent to a .10 blood alcohol level. Worse: most people who’ve fallen into this state typically have no idea of just how impaired they are. It’s only when you look at the dramatically lower quality of their output that it shows up. Robinson writes: “If they came to work that drunk, we’d fire them — we’d rightly see them as a manifest risk to our enterprise, our data, our capital equipment, us and themselves. But we don’t think twice about making an equivalent level of sleep deprivation a condition of continued employment.”

…

For employees, the fundamental realization is that an employer who asks for more than eight hours a day or 40 hours a week is stealing something vital and precious from you. Every extra hour at work is going to cost you, big time, in some other critical area of your life. How will you make up the lost time? Will you ditch dinner and grab some fast food? Skip the workout? Miss the kids’ game this week? Sleep less? (Sex? What’s that?) And how many consecutive days can you keep making that trade-off before you are weakened in some permanent and substantial way? (Probably not as many as you think.) Changing this situation starts with the knowledge that an hour of overtime is a very real, material taking from our long-term well-being — and salaried workers aren’t even compensated for it.

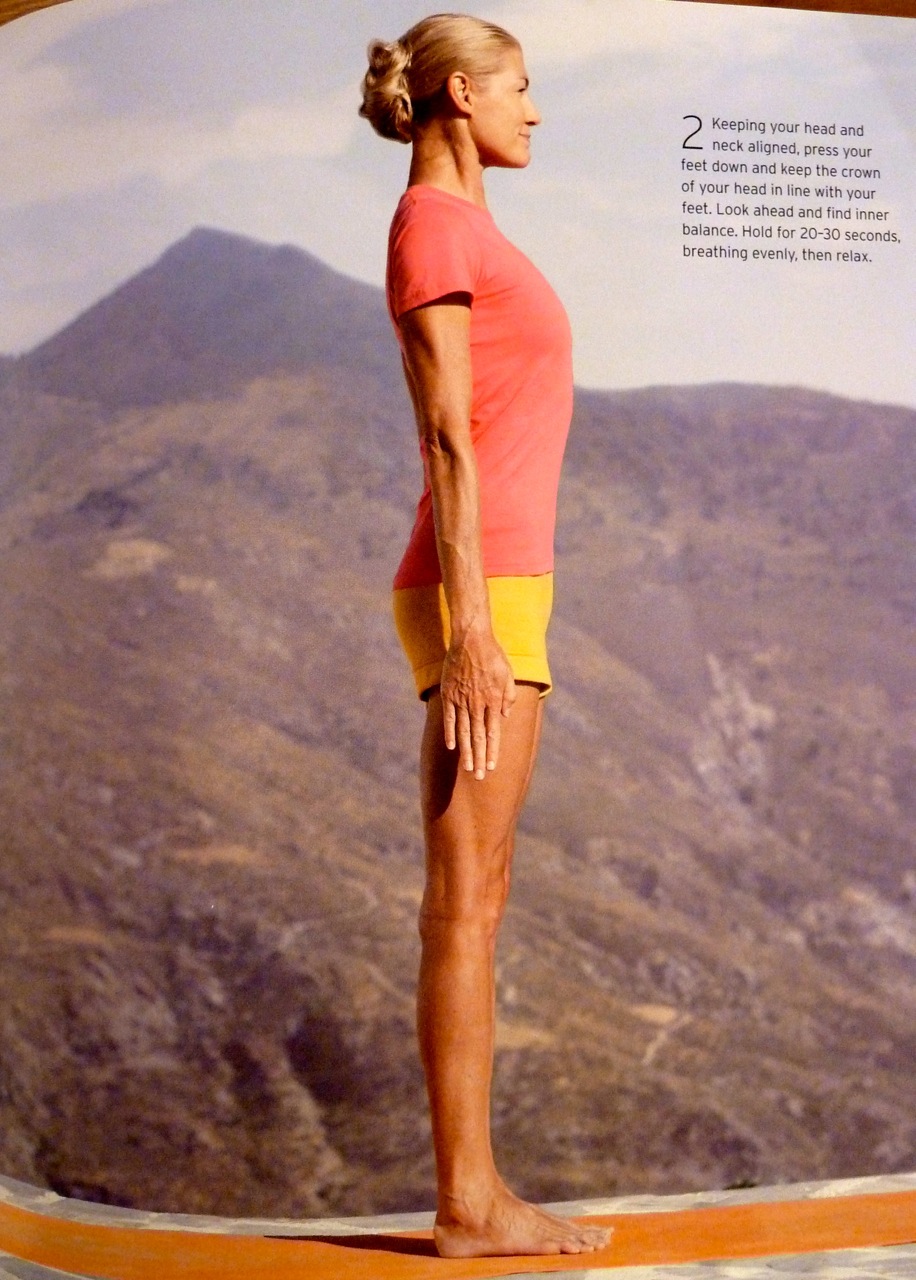

There are now whole industries and entire branches of medicine devoted to handling workplace stress, but the bottom line is that people who have enough time to eat, sleep, play a little, exercise and maintain their relationships don’t have much need of their help. The original short-work movement in 19th-century Britain demanded “eight for work, eight for sleep and eight for what we will.” It’s still a formula that works.

…

Working long days and weeks has been incontrovertibly proven to be the stupidest, most expensive way there is to get work done. Our bosses are depleting resources from of the human capital pool without replenishing them. They are taking time, energy and resources that rightfully belong to us, and are part of our national common wealth.

If we’re going to talk about creating a more sustainable world, let’s start by talking about how to live low-stress, balanced work lives that leave us refreshed, strong and able to carry on as economic contributors for a full four or five decades, instead of burned out and broken by a too-early middle age. A full, productive 40-year career starts with full, productive 40-hour weeks. And nobody should be able to take that away from us, not even for the sake of a paycheck.